The deployment of the world’s first polymer banknotes in 1988 was so successful that it appeared to many to be an overnight success. One day we were using paper banknotes, the next we were handling notes made from plastic. The notes were so finished, with complete designs, nation-wide distribution and even a publicity campaign, that there was little thought given to the process that led to that point.

Truly innovative technology doesn’t just come into existence overnight of course, the evolution of the technology used to print Australia's polymer banknotes can be traced back to a series of counterfeit paper $10 notes discovered in 1966.

Once all of those counterfeit $10 notes had been tracked down and destroyed, once the perpetrators that had printed them had been put behind bars, the Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, Dr Herbert (Nugget) Coombs, resolved to ensure those unseemly events were never repeated.

Nugget was convinced that science should be able to put much more distance between what the forgers were apparently so easily able to simulate, and what the bank could produce.

A think tank was formed in 1968 to discuss the challenge, and was made up of several scientists from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) as well as a number of universities.

In total, Coombs enlisted seven top Australian scientists – five physicists and two chemists. The two chemists were Jerry Price (who went on to become chairman of CSIRO), and Sefton Hamann, chief of the CSIRO Division of Applied Chemistry.

One of the key points taken away from this first meeting, made by a representative from Kodak Australia, was that if the new banknotes could be photographed, they could also be printed and forged.

For this reason, the scientists in the think tank resolved to come up with a security device that couldn't be photographed (and thus couldn't be forged), and it is from this idea that the optically variable device (OVD) was born.

David Solomon - Senior Principal Research Scientist at CSIRO and Principal Inventor of the Polymer Note

David Solomon was Senior Principal Research Scientist at CSIRO, he led the CSIRO team that developed the use of plastic films and OVDs. His industrial achievements are best exemplified by the Australian Bicentennial $10 banknote, where he was a principal inventor as well as the project leader from the inception through to the technology transfer stage of the project. Among Solomon's published recollections of the early days of the development of polymer banknote technology is the following statement:

"We produced these devices in large quantities to demonstrate the practical nature of the concept.

We built a production plant in secret and printed a design provided by the RBA – birds in flight – using our plastic film.

However the number of ideas was beginning to confuse the Reserve Bank and a freeze was put on further designs. So we focused on Diffraction gratings (Holograms), Moire interference patterns, photochromic compounds and a label.

It was around that time that Solomon then proposed a massive innovation - to print notes on clear plastic film, rather than paper. Just the presence of a clear area within the body of the note would force potential forgers to use plastic - at that time at least, clear film was not commercially available.

Solomon's group at CSIRO made their own polymer substrate, a product that was unique in the world.

After it had been made opaque, the laminate developed by CSIRO could be printed on using conventional printing machines. After the laminate had been printed, security features were applied.

The most notable features of the early test notes were described as being the see-through panel and the hologram.

Testing Conducted in Port Melbourne In Secret

At one stage, Solomon's team included no less than 31 staff. In secret at a shed at the CSIRO's Port Melbourne site, they built a pilot production line and produced the equivalent of 50 million banknotes. and 1.25 million OVDs - this was to prove to the Reserve Bank that these revolutionary ideas were not only innovative, but were also practical - that the notes could be produced economically.

The testing of the substrate, laminate and security devices was a particular challenge. As any and all issues regarding printing need to be resolved before any notes enter circulation, it obviously isn't possible to issue them into circulation, then wait for problems to present themselves, and fix them after that.

The Turbula - Kerosene, Dirt and Artificial Sweat

One piece of lab equipment the secret team at CSIRO used to measure the durability of their polymer test notes was called the "Turbula", a machine that simulated the rigours of circulation. The testing process involved placing weights in the corners of each of the test notes, and then tumbling them in a kerosene drum containing controlled amounts of synthetic dirt (carbon black), abrasive materials (polypropylene beads) and even artificial sweat.

This process was apparently extremely accurate at predicting the field performance of the new notes, and was also used in later stages of quality control.

Published anecdotes that describe this phase of testing indicate that it was conducted from the mid 1970's - all technical problems are known to have been largely solved in about 10 years, which would indicate that lab testing was complete perhaps by the mid-1980's. The world's first polymer banknotes were actually issued into circulation in our Bicentennial year, 1988.

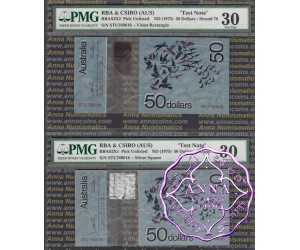

The test notes photographed above are unequivocally the same type of note used by Solomon and his team in testing various substrates, printing laminates and security devices. Similar test notes can be seen in CSIRO's own images of the Turbula durability test, as well as in library images of David Solomon.

Rather dismissing these test notes based on their condition, I'd suggest collectors view them as being an authentic representation of the lengths to which the CSIRO went to ensure the integrity of our national currency. They've been through the Turbula and have survived after all!

The test notes that I have sighted have a texture unlike any polymer note printed for circulation.

As can be seen from the images of the polymer test notes posted here, the simultan print phase seems to have been the easiest print phase for CSIRO to master - although they're subdued, the background colours have survived largely intact.

The sharpness of the intaglio design - the "exaltation" of larks, as well as the written notations of the denomination etc, are of course printed more sharply on the notes we use today.

The biggest challenge for the Solomon's secret CSIRO testing team seems to have been the hologram - the honeycomb texture to the Mark 1 note clearly indicates improvement was necessary.These polymer test notes will be of keen interest to anyone committed to building a collection that showcases the evolution of circulating currency in Australia. They are a rare, direct and tangible representation of Australia's worldwide reputation for innovation and integrity in this incredibly challenging field.

-140x140.jpg)